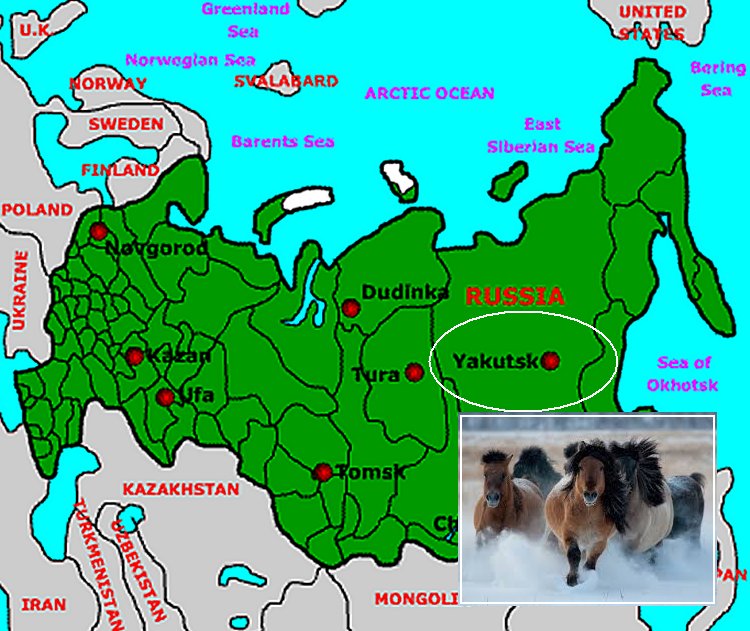

A Tale Of Yakutian Horses: One Of The Fastest Cases Of Adaptation To – 70 Degrees In Siberia

MessageToEagle.com – In less than 800 years Yakutian horses adapted to temperatures of -70 degrees found in the extreme environments of eastern Siberia.

This is one of the fastest examples of adaptation within mammals.

The adaptation mechanisms involved the same genes found in humans as well as the extinct wooly mammoth.

A new study based on the comparison of the complete genomes of nine living and two ancient Yakutian horses from Far-East Siberia with a large genome panel of 27 domesticated horses reveals that the current population of Yakutian horses was founded following the migration of the Yakut people into the region in the 13-15thcentury AD.

See also:

Ancient DNA: So Far Oldest Genome From A 700.000 Year Old Horse – Sequenced

Horses have been essential to the survival and development of the Yakut people, who migrated into the Far-East Siberia in the 13-15th century AD, probably from Mongolia. There, Yakut people developed an economy almost entirely based on horses.

Horses were very important for communication and keeping population contact within a territory slightly larger than Argentina, and with 40 % of its surface area situated north of the Arctic Circle. Horse meat and hide have also revealed crucial for surviving extremely cold winters, with temperatures occasionally dropping below -70C.

Yet, Dr. Ludovic Orlando from the Centre for GeoGenetics at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen and his team now reveal that ancient horses of this region were not the ancestors of the present-day Yakutian horses.

The genome sequence obtained from the remains of a 5,200 year-old horse from Yakutia appears within the diversity of a now-extinct population of wild horses that the team discovered last year in Late Pleistocene fossils from the Taymir peninsula, Central Siberia.

This new finding extends by thousands of kilometers eastwards the geographical range of this divergent horse population, which became separated from the lineage leading to modern horses some 150,000 years ago. It also extends its temporal range up to 5,200 years ago, a time when woolly mammoths also became extinct.

“This population did not appear on any radar until we sequenced the genomes of some of its members.

With 150,000 years of divergence with the lineage leading to modern horses, this makes the roots of this population as deep as the origins of our human species,” Dr. Ludovic Orlando says.

Interestingly, the new genome analyses show that the horses that Yakut people now ride and probably rode all along their history (as shown by the genome of a ~200 year-old horse), are not related with this now-extinct horse lineage, but rather with the domesticated horses from Mongolia. Dr. Ludovic Orlando says:

“We know now that the extinct population of wild horses survived in Yakutia until 5,200 years ago. Thus it extended from the Taymir peninsula to Yakutia, and probably all across the entire Holarctic region. In Yakutia, it may have become extinct prior to the arrival of Yakut people and their horses. Judging from the genome data, modern Yakutian horses are no closer to the extinct population than is any other domesticated horse.”

The findings are published in the PNAS.

MessageToEagle.com