Ancient Material From The Mysterious Vitrified Broborg Hill-Fort Can Offer Nuke Waste Solutions

MessageToEagle.com – Vitrified forts are remnants of stony fortifications in which rock fragments or boulders have been melted and/or welded together by extreme heat. What exactly is behind the vitrification process, remains unknown. Now scientists are studying ancient material from the mysterious vitrified Broborg hill-fort with the hope ancient technology can offer new nuke waste solutions.

Scientific Theories About Vitrification

There are many vitrified ruins and forts across the world. How and why they are created remains unknown, although several theories have been put forward. Scientists have been studying vitrified since the late 18th century and currently there are three hypotheses that could explain the virtification process.

One possibility is that the vitrified material is interpreted as being volcanic lava or pumice used in construction. Alternatively, vitrification is considered to be an incidental effect resulting from signal-fires, bonfires, cooking-hearths or forges.

Another possibility is that suitable rocks and a fud material, such as wood or charcoal, have been mixed and burned. This process could have taken place either in situ, or in specially erected furnaces, from which the material was withdrawn and used for “casting” the ramparts. The purpose was constructive in the sense that the outcome was a more resistant construction.

The third option also proposed by scientists is that a timber-laced wall (e.g. of the murus galliens type) was set on fire by enemies or by accident (e.g. lightning). Under certain conditions, the fire resulted in temperatures sufficient to melt/calcine the building material. The outcome was that the fortification was, at least in part, destroyed.

Mysterious Vitrified Broborg Hill-Fort

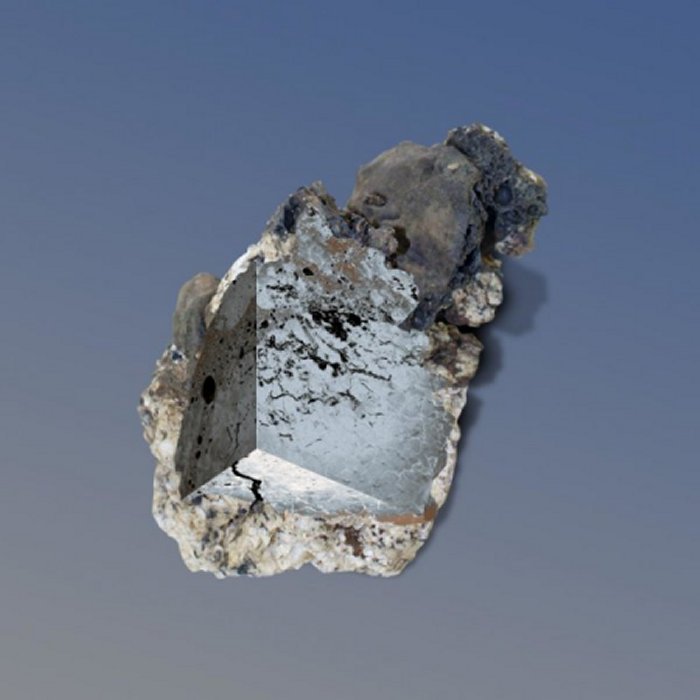

Broborg hill-fort is located about 20 southeast of Uppsala, Sweden. In 1982, Broborg was partly excavated. It was concluded the vitrified fort is from the early Iron Age. The most characteristic feature of Broborg is the omnipresent vitrification of the wall. The wall seems to have been a standing drystone wall, made of rather large boulders, with an inner upcast gravel rampart. In the southern and eastern parts an outer dry-stonewall complements the inner wall.

No vitrification has been observed in the outer wall. The main entrance to the fort was the gate in the south-east. Vitrification can be seen at many places around the inner wall. Often the vitrified wall has a much smoother relief than the non vitrified sections. Temperature required for vitrification is about 1130°C, with low oxygen fugacities.

Ancient Vitrified Material Can Offer Nuke Waste Solutions

Researchers at Washington State University looking back at ancient materials from around the world hoping to find new nuke waste solutions.

At the Hanford nuclear site in eastern Washington, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) is building the world’s largest radioactive waste treatment plant for cleanup of 56 million gallons of radioactive and chemical waste. Researchers want to convert the waste, held in underground storage tanks, into durable glass that can be stored for thousands of years.

Credit: Washington State University photo

But they need to improve their understanding of how that glass would corrode, perform and alter over such a long time.

Led by Jamie Weaver, a WSU doctoral student in chemistry, the researchers are studying materials from the mysterious Broborg hill-fort in Sweden, where a tribe of people around 1,500 years ago melted rocks to strengthen fortifications against invaders. They piled boulders left by ancient glaciers into two large rings, put black amphibolite rocks on top, layered the wall with charcoal and burned it. As the rock melted, it infiltrated the boulders and cooled as glass, acting as glue for the wall.

“The technique is like nowhere else in the world,” said John McCloy, associate professor in the WSU School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering and co-author on the paper. “They heated the rock until it melted and it is still quite intact 1,500 years later.”

See also:

Ancient Sophisticated Technologies: Mercury-Based Gilding That We Still Can’t Reach

The Broborg site is valuable because researchers know what happened to the glass, how old it is and how it has worn. This can help them improve their models for long-term environmental protection, he said: “We need relevant timescales.”

If scientists managed to get to the bottom with what’s behind the vitrification process, the results of the study could change and improve our environment in relation to nuke waste storage.

MessageToEagle.com