People Who Predated Clovis Culture And Were Present In America Earlier Than Previously Thought

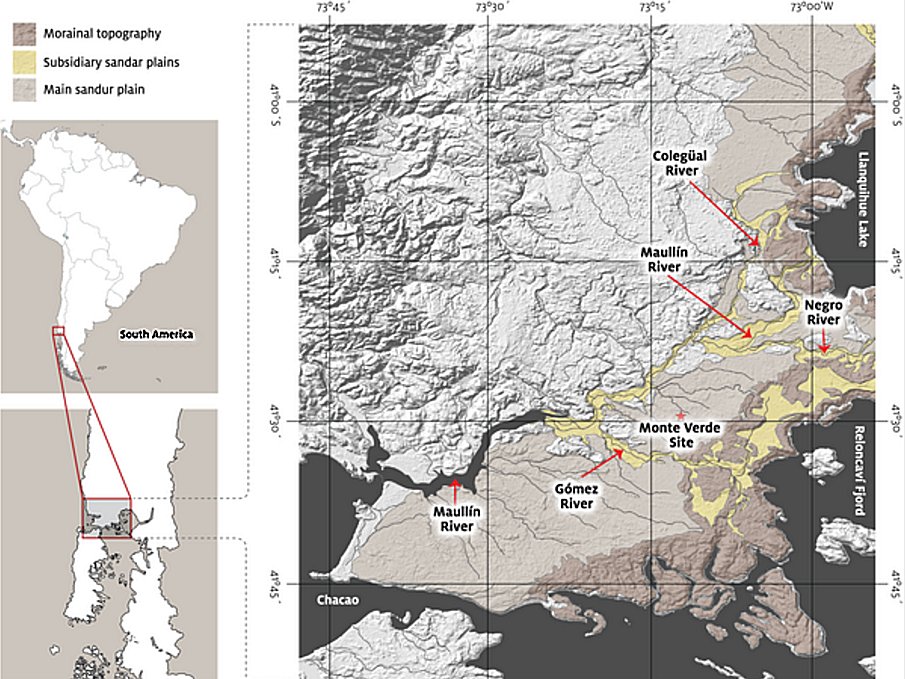

MessageToEagle.com – An international team of archaeologists, geologists and botanists performed an archaeological and geological survey of Monte Verde in southern Chile and found stone tools, cooked animal and plant remains and fire pits.

These archaeological findings in Chile provide important evidence that the earliest known Americans – a nomadic people adapted to a cold, ice-age environment – were established deep in South America more than 15,000 years ago.

For the past 40 years it has been supposed that the first people to arrive in the Americas were hunters – today known as the Clovis culture – who crossed a land bridge from Asia to North America around 12,000-13,000 years ago and used a distinctive type of fluted stone projectile point called Clovis points.

However, Professor Tom Dillehay, an anthropologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville Tennessee, who has worked at Monte Verde since 1977, found new evidence in form of an entirely different type of stone tool technology used by people who predated the Clovis culture by about 1,500 years.

“We began to find what appeared to be small features—little heating pits, cooking pits associated with burned and unburned bone, and some stone tools scattered very widely across an area about 500 meters long by about 30 or 40 meters wide,” said Dillehay.

The team recovered a total of 39 stone objects and 12 small fire pits associated with bones and some edible plant remains, including nuts and grasses. The bones tended to be small fragments, broken and scorched, indicating that the animals had been cooked.

They often came from very large animals, like prehistoric llamas or mastodons, as well as smaller creatures like prehistoric deer and horses. The Monte Verde site was unlikely to have been able to support the kind of vegetation that those animals needed to eat, so they were likely killed and butchered elsewhere.

“One of the curious things about it that is that unlike what we found before, a significant percentage, about 34 percent, were from non-local materials. Most of them probably come from the coast but some of them probably come from the Andes and maybe even the other side of the Andes,” said Dillehay. Prior research had revealed evidence of Andean plants in the area, providing further support for a highly mobile population.

The objects were radiocarbon dated and most were found to range in age from more than 14,000 to almost 19,000 years old.

The wide scattering suggests that the people who created these features were nomadic hunter-gatherers who might have camped for only a night or two before moving on.

“Where they’re going, we don’t know, and where they’re coming from, we don’t know, but this would have been a passageway from the coast to the foothills of the Andes,” Dillehay said.

Dillehay believes that they may have come through Monte Verde because the terrain was more walkable than the surrounding bogs and wetlands, and because it provided access to stone to make tools.

At the end of the last ice age, Monte Verde was situated about six kilometers away from a glacier, which had begun to retreat, but still, a non-glacial cold climate environment of the south-central Andes, was challenging for human occupation and for the preservation of hunter-gatherer sites in northern Patagonia.

The research, led by led by Tom Dillehay, Rebecca Webb Wilson University Distinguished Professor of Anthropology, is published in the Nov. 18 issue of PLOS One.

MessageToEagle.com

source: Vanderbilt University