Incredible Ancient Metallurgical Wonders That Defy Explanation And Pose A Real Mystery Even Today

MessageToEagle.com – The Antediluvians had technologies that matched our own; there are also serious indications that in certain areas they even possessed extraordinary knowledge, which has only hardly been nudged by our present-day science.

Highly advanced hardening techniques of the ancients as well as ancient castings of large pieces, were widespread in antiquity.

Our ancestors were in possession of an extremely sophisticated scientific knowledge of metalworking from an earlier civilization and evidence of this knowledge was found in different parts of the world.

China with a long history in metallurgy, was the earliest civilization that manufactured cast iron and some of the ancient Chinese feats of casting iron are so impressive as to be almost unbelievable.

One of them is for example, the cast iron pagoda entirely built of cast iron at Dangyang, Hubei Province, China, in 1061. It is the tallest (17.9 m high) surviving cast-iron structure, which has 13 stories, built up of cast-iron octagonal sections fitted together by a tenon-and-mortise system.

One large sculpture of legendary fame is the majestic cast-iron lion situated not far from the Grand Canal at Cangzhou, Hebei Province. It was manufactured in 953 AD.

The gigantic lion (5.4×3×5.3 m) weighs over 37 tons. It is hollow and the thickness of its walls varies from 40 to 20 cm. On its back is a lotus pedestal of cast iron weighing circa 5 tons.

“The mystery of the use of iron in India and China is one that largely baffles modern metallurgists. It is assumed that these countries developed iron and other metallurgical skills after the west, but the evidence points otherwise,” says D. H. Childress in his book “Technology of the Gods: The Incredible Sciences of the Ancients” and cites South African archaeologist Nikolass van der Merwe, saying that “spreading east from the Mediterranean, iron was diffused throughout most of Asia before the Christian era.

“By 1100 BC it was in use in Persia, from where it spread to Pakistan and India. The date of the arrival of iron in India is still a matter of some dispute…”

Ancient Indians, for example, produced iron capable of withstanding corrosion, most likely due to the high phosphorus content of the iron produced during those times.

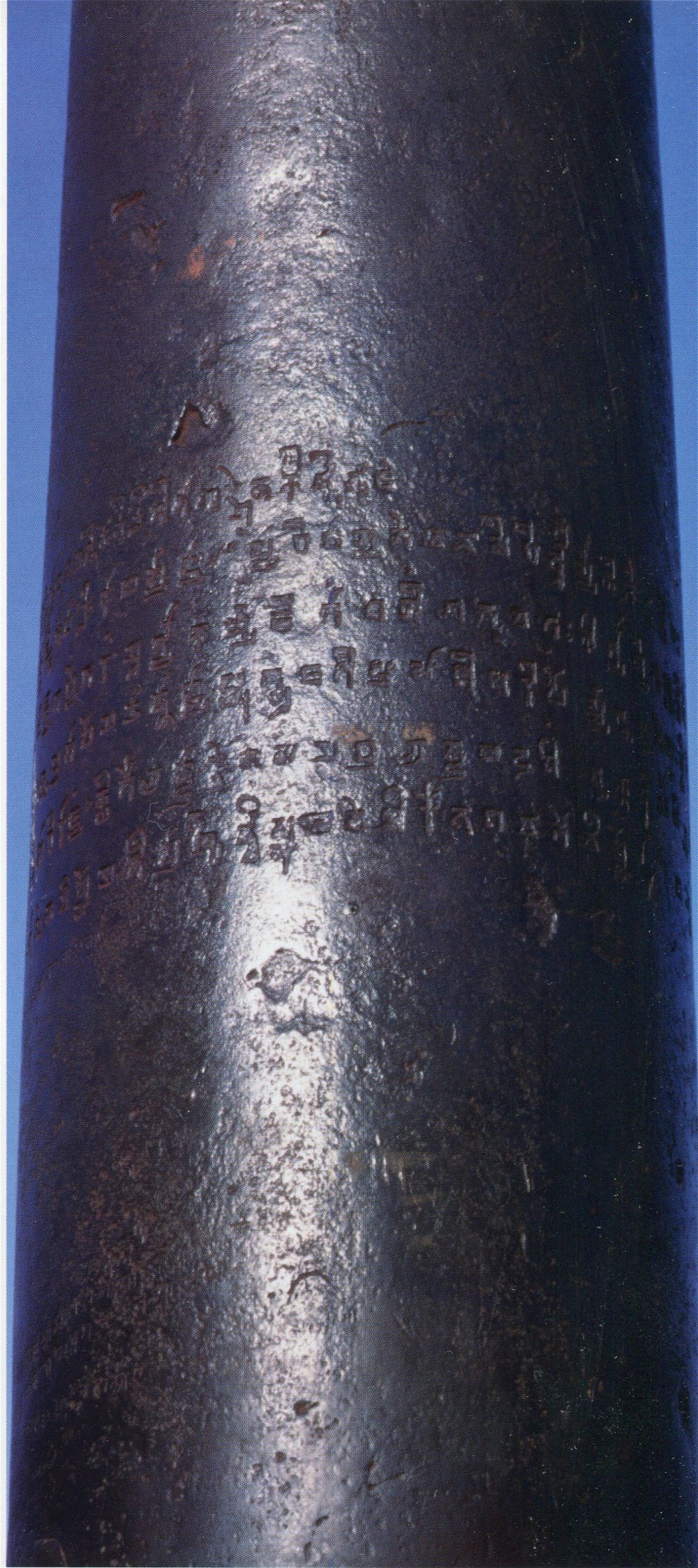

A column of cast iron 23 feet (7 meters) high, weighing approximately 6 tons with diameter of 16.4 inches stands in the courtyard of Kutb Minar in Delhi, India.

An inscription in the Sanscrit language informs that the column was originally erected in the temple of Muttra and capped with Garuda – “Messenger of the Gods” – an image of the bird incarnation of the god Vishnu, the Indian god known as “The Preserver”.

But Muslim invaders destroyed the Garuda and tore the column from its original setting and moved it to the current place in Delhi in the eleventh century.

It is unknown how long this impressive iron shaft had been at Muttra.

What was it meant to represent?

Was it merely a religious symbol or did it serve any other purpose?

To which era does the pillar really belong?

Many legends are devoted to the Ashoka Pillar also known as the Iron Pillar in Delhi, which is said to be in existence for the past 1600 years, but some scholars believe the structure is a few millennia old.

This metallurgical wonder defies explanation and poses a real mystery even today, due to its enormous size and a sizeable casting job related to it. It is difficult to even imagine how such a huge mass of iron was lifted and manipulated during manufacture.

How did the structure manage to “survive” under the Indian tropical heat and violent monsoon downpours.

See also:

- Ancient Sophisticated Technologies: Mercury-Based Gilding That We Still Can’t Reach

- Advanced Ancient Technology: Could Ancient Peruvians Soften Stone?

- Did Ancient Civilizations Possess Knowledge Of Time Travel?

Normally a piece of iron manufactured 1600 years ago would have corroded long ago. But it is not the only mystery of the Ashoka Pillar.

The column – made up of 98% wrought iron of impure quality – not in any way welded together – seems to have been forged as a single, gigantic piece of iron.

Iron with exceptionally high purity can be produced today under controlled laboratory conditions by electrolysis. This knowledge was not duplicated until recent times.

It was even possible to produce iron of comparable purity in 1938.

Fabrication of the Iron Pillar, seven-ton heavy and seven meter tall known for its amazing corrosion resistance despite exposure to the wind, sun and rain in the open for more than 16 centuries is undoubtedly metallurgical marvel of the ancients.

How metallurgists of ancient India achieved this level of iron purity and what kind of technique they used to cast such enornous iron pillar – remains a mystery.

Another mysterious iron column exists at Kottenforst, a few miles west of Bonn, Germany. It has its local name the “Iron Man”. It has the appearance of a squared metal bar, with 4 feet 10 inches above ground and an estimated 9 feet beneath the surface.

Like the iron pillar of India, the “Iron Man” of Kottenforst shows some weathering but very little trace of rust.

Who made it, how and why, is unknown.

Copyright © MessageToEagle.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of MessageToEagle.com

Related Posts

-

Coyote: Hero, Trickster, Immortal And Respected Animal In Native American Myths

No Comments | May 14, 2016

Coyote: Hero, Trickster, Immortal And Respected Animal In Native American Myths

No Comments | May 14, 2016 -

Crimean Atlantis: Remarkable Ancient Underwater City Of Akra

No Comments | Mar 6, 2017

Crimean Atlantis: Remarkable Ancient Underwater City Of Akra

No Comments | Mar 6, 2017 -

Ziggurats, Axis Mundi And Strong Connection To Religion In Mesopotamia

No Comments | Mar 18, 2021

Ziggurats, Axis Mundi And Strong Connection To Religion In Mesopotamia

No Comments | Mar 18, 2021 -

Striking Hindu Temples – Maya And Sumer Connection

No Comments | Jan 25, 2015

Striking Hindu Temples – Maya And Sumer Connection

No Comments | Jan 25, 2015 -

Is Legendary Norumbega In North America A Lost Viking Settlement?

No Comments | Jan 9, 2021

Is Legendary Norumbega In North America A Lost Viking Settlement?

No Comments | Jan 9, 2021 -

Mystery Of The Pre-Adamic Didanum Race: Giants Who Were Ancestors Of The Nephilim and Rephaim

No Comments | Oct 2, 2014

Mystery Of The Pre-Adamic Didanum Race: Giants Who Were Ancestors Of The Nephilim and Rephaim

No Comments | Oct 2, 2014 -

King Tut’s Cosmic Scarab Brooch And Dagger Linked To Meteorite’s Crash 28 Million Years Ago

No Comments | Jun 24, 2021

King Tut’s Cosmic Scarab Brooch And Dagger Linked To Meteorite’s Crash 28 Million Years Ago

No Comments | Jun 24, 2021 -

Controversial Tartaria Tablets: The First Writing System In The World?

No Comments | Nov 13, 2014

Controversial Tartaria Tablets: The First Writing System In The World?

No Comments | Nov 13, 2014 -

Daily Life Of A Lady In Waiting – A Dangerous Profession Sometimes

No Comments | Sep 22, 2023

Daily Life Of A Lady In Waiting – A Dangerous Profession Sometimes

No Comments | Sep 22, 2023 -

2000 Ancient Gold Spirals Used By Sun-Worshiping Priest-Kings During The Bronze Age Discovered In Denmark

No Comments | Jul 9, 2015

2000 Ancient Gold Spirals Used By Sun-Worshiping Priest-Kings During The Bronze Age Discovered In Denmark

No Comments | Jul 9, 2015