Controversial Grolier Codex: 13th Century Maya Codex Is Genuine

MessageToEagle.com – Ever since its discovery in the 1960s, the Grolier Codex has been a subject of controversy.

This ancient document that is among the rarest books in the world was found by looters in cave in Chiapas, Mexico, but was the Codex genuine?

A new study now reveals that not only is the 13th century Maya Codex genuine, but it is also the most ancient of all surviving manuscripts from ancient America!

The study carried out by a group of scientists from the Brown University, Harvard and the University of California-Riverside. The research team has named their science paper “The Fourth Maya Codex”.

For years, academics and specialists have argued about the legitimacy of the Grolier Codex, but scientists are now totally convinced this ancient document is real.

“It is a confirmation that the manuscript, counter to some claims, is quite real. The manuscript was sitting unremarked in a basement of the National Museum in Mexico City, and its history is cloaked in great drama.

It was found in a cave in Mexico, and a wealthy Mexican collector, Josué Sáenz, had sent it abroad before its eventual return to the Mexican authorities,” said Stephen Houston, the Dupee Family Professor of Social Science and co-director of the Program in Early Cultures at Brown University.

The codex was reportedly found in the cave with a cache of six other items, including a small wooden mask and a sacrificial knife with a handle shaped like a clenched fist, the authors write. They add that although all the objects found with the codex have been proven authentic, the fact that looters, rather than archeologists, found the artifacts made specialists in the field reluctant to accept that the document was genuine.

See also:

Dresden Codex – The Oldest And Best Preserved Book Of The Maya

Codex Borgia: Pre-Columbian Mexican Manuscript Of Great Importance

Some ridiculed as fantastical Sáenz’s account of being contacted about the codex by two looters who took him — in an airplane whose compass was hidden from view by a cloth — to a remote airstrip near Tortuguero, Mexico, to show him their discovery.

And there were questions, the authors note, about Sáenz’s actions once he possessed the codex. Why did he ship it to the United States, where it was displayed in the spring of 1971 at New York City’s Grolier Club, the private club and society of bibliophiles that gives the codex its name, rather than keep it in Mexico? As for the manuscript itself, it differed from authenticated codices in several marked ways, including its relative lack of hieroglyphic text and the prominence of its illustrations.

“It became a kind of dogma that this was a fake,” Houston continued. “We decided to return and look at it very carefully, to check criticisms one at a time. Now we are issuing a definitive facsimile of the book. There can’t be the slightest doubt that the Grolier is genuine.”

Grolier Codex differs from the three other known ancient Maya manuscripts. The Dresden, Madrid and Paris, all named for the cities in which they are now housed all have calendrical and astronomical elements that track the passage of time via heavenly bodies, assist priests with divination and inform ritualistic practice as well as decisions about such things as when to wage war.

The Grolier was dated by radiocarbon and predates those codices, scientists say.

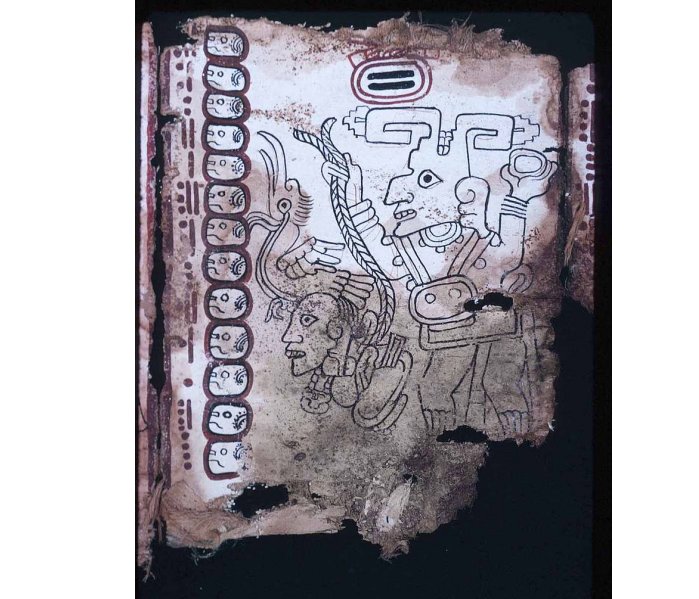

Credit: Justin Kerr

The Grolier’s composition, from its 13th-century amatl paper, to the thin red sketch lines underlying the paintings and the Maya blue pigments used in them, are fully persuasive, the authors assert.

The Maya Blue has been a scientific puzzle mainly due to its unusual chemical composition. Maya blue is an extremely resistant artificial pigment. Despite time and the harsh weathering conditions, paintings colored by Maya blue have not faded over time. However, the blue pigment could be destroyed using very intense acid treatment under reflux.

The Maya Blue (azul maya in Spanish) has been discovered at several architectural locations from the ancient Mayan civilization including the archaeological site of Cacaxtla on the Mural de la batalla.

The Grolier Codex is a fragment, consisting of 10 painted pages decorated with ritual Maya iconography and a calendar that charts the movement of the planet Venus. Mesoamerican peoples, Houston said, linked the perceived cycles of Venus to particular gods and believed that time was associated with deities.

The Venus calendars counted the number of days that lapsed between one heliacal rising of Venus and the next, or days when Venus, the morning star, appeared in the sky before the sun rose. This was important, the authors note, because measuring the planet’s cycles could help Maya people create ritual cycles based on astronomical phenomena.

The gods depicted in the codex are described by Houston and his colleagues as “workaday gods, deities who must be invoked for the simplest of life’s needs: sun, death, K’awiil — a lordly patron and personified lightning — even as they carry out the demands of the ‘star’ we call Venus. Dresden and Madrid both elucidate a wide range of Maya gods, but in Grolier, all is stripped down to fundamentals.”

That places the Grolier in a different tradition than the Dresden Codex, which is known for its elaborate notations and calculations, and makes the Grolier suitable for a particular kind of readership, one of moderately high literacy. It may also have served an ethnically and linguistically mixed group, in part Maya, in part linked to the Toltec civilization centered on the ancient city of Tula in Central Mexico.

Beyond its useful life as a calendar, the Grolier Codex “retained its value as a sacred work, a desirable target for Spanish inquisitors intent on destroying such manuscripts,” the authors wrote in the paper.

Created around the time when both Chichen Itza in Yucatán and Tula fell into decline, the codex was created by a scribe working in “difficult times,” wrote Houston and his co-authors. Despite his circumstances, the scribe “expressed aspects of weaponry with roots in the pre-classic era, simplified and captured Toltec elements that would be deployed by later artists of Oaxaca and Central Mexico” and did so in such a manner that “not a single detail fails to ring true.”

“A reasoned weighing of evidence leaves only one possible conclusion: four intact Mayan codices survive from the Precolumbian period, and one of them,” Houston and his colleagues wrote, “is the Grolier.”

MessageToEagle.com